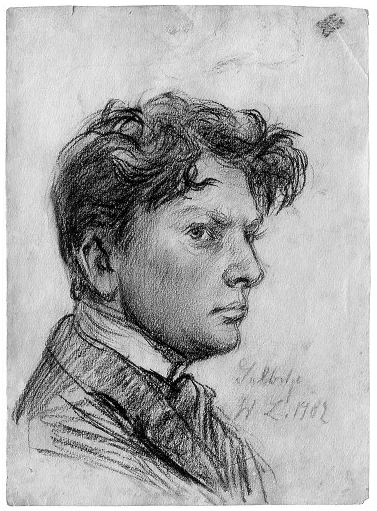

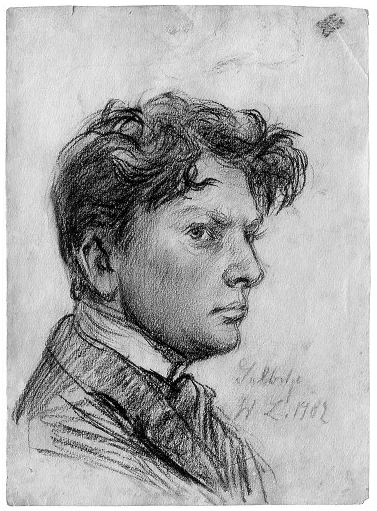

Wilhelm Lehmbruck

Image from Wikipedia

Image from Wikipedia

Wilhelm Lehmbruck – The Quiet Revolutionary of Modern Sculpture

Between Melancholy and Monument: How a Sculptor from Duisburg Reinvented the Figure of Modernity

Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881–1919) is among the most significant sculptors of classical modernism. His slender, elongated figures, his ascetic visual language, and the psychological depth of his compositions transformed the perception of the human form in the 20th century. Coming from humble beginnings in the Ruhr area, he developed a distinctive artistic style that oscillates between realism and expressionism, captivating international museums, curators, and art historians to this day.

His artistic career took him from Düsseldorf to Paris and then to Berlin and Zurich, passing through the key centers of European art life—shaping his artistic development. Encounters with the avant-garde, the experience of World War I, and a radical will to reduce his works significantly influenced his oeuvre. Overall, Lehmbruck's work represents a new aesthetics of sensibility, the spatial presence of which—the quiet tension of bodies, the controlled pathos—became iconic.

Childhood, Education, and the Search for Form (1881–1906)

Born on January 4, 1881, in Meiderich near Duisburg, Lehmbruck showed early drawing talent. He honed his skills in craftsmanship, composition, and plastic anatomy at the Düsseldorf School of Applied Arts and later as a master student at the Academy of Arts. Early works such as Bathers (1905) still bear the weight of academic traditions and the monumental impact of Auguste Rodin, while already displaying a tendency toward the simplification of volumes. During this phase, Lehmbruck experimented with material changes, from plaster to stone casting or bronze, and refined his understanding of proportion, scale, and static balance.

Important exhibitions from 1906 onward and connections with collectors and institutions made his work visible beyond Düsseldorf. These years laid the foundation for his artistic development: a steady departure from decorative fullness in favor of clear, calm silhouettes, a condensation of the figure into carriers of inner states, and a growing interest in the expressive power of the body.

Paris and the International Breakthrough (1910–1914)

In 1910, Lehmbruck moved to Paris—a turning point in his artistic journey. Here, he encountered Aristide Maillol, Amedeo Modigliani, and other protagonists of modernism. The encounter with French sculpture fostered a shift towards calm, closed volumes that radiate both distance and introspection. Works like Standing Female Figure (1910) or Kneeling (1911) mark the moment when Lehmbruck perceives the figure as a resonance space for emotional states: the gaze slightly lowered, the limbs elongated, the surface dematerialized.

His participation in the Cologne Sonderbund exhibition (1912) and especially in the Armory Show in New York, Chicago, and Boston (1913) garnered Lehmbruck international attention. Kneeling became a key work: an emblem of expressive sculpture that, through its ascetic concentration, shaped the pathos formula of modernity. The formal language—abstraction of details, elongation as a carrier of expression, a choreographed dialogue of statics and space—now achieved strict consistency.

War, Hospital, and the Existential Turn (1914–1916)

With the outbreak of World War I, Lehmbruck returned to Germany. He served as a medic in Berlin, experiencing the suffering of the wounded firsthand. This shock catalyzed a deep, artistically productive crisis: the figures became more fragile, the gestures heavier, the expressions more existential. Sculptures like The Fallen (1915/16) articulate a radical anti-war gesture—an falling, curved body that transforms pain, guilt, and sorrow into pure form.

At the same time, Lehmbruck refined his sculptural grammar: axis shifts, negative spaces, and the conscious understatement of heroic gestures. Reduction became an ethos. The body speaks—not as an anatomical study, but as a bearer of metaphysical experience. This is the true artistic development of Lehmbruck: from classic volume to spiritual figure.

Zurich, Late Works, and Tragic End (1916–1919)

At the end of 1916, Lehmbruck left Berlin for Zurich, where a productive yet mentally strained late phase began. Works like Seated Youth (1916/17) or Seated (1917/18) condense the melancholic mood into an almost iconic pose of introspection. The surfaces are still, the gestures minimal, the proportions deliberately estranged—a metaphysical visual language that transforms the theme of loneliness into a universal form.

In 1919, Lehmbruck was appointed to the Prussian Academy of Arts—a late sign of official recognition. On March 25, 1919, he took his own life in Berlin. The tragedy of his early death intensified the aura of his work, yet his influence on modern sculpture remains alive and institutionally anchored—not least through the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, designed by his son, architect Manfred Lehmbruck.

Work, Style, and Technique: The Language of Reduction

Lehmbruck's artistic development can be described as a consistent reduction: moving away from naturalistic modeling towards tectonically clear, ascetic bodies. His figures define themselves through vertical tension, elongated proportions, a sensitive balance of weight and lightness. In production, he used plaster, stone casting, bronze, and occasionally stone; translating the sculptural idea into different materials was important to vary surface impact, weight, and spatial relationship.

Compositional, Lehmbruck worked with sight axes that allow the viewer to move around them: tilted heads, spirally directed arm positions, knee and bend lines that unite into an inner statics. Thus arises the paradox of his sculptures: outwardly calm, internally vibrating. In art historical classification, he stands between Maillol's classical closure and the spiritual expressiveness of expressionism—a distinct position that has profoundly shaped the perception of the modern figure.

Major Works and Reception: From the “Kneeling” to the “Fallen”

Kneeling (1911) is his most famous work and was exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913 in the USA; it established Lehmbruck's international reputation. Various versions and casts can be found in museum collections, illustrating the significance of the sculpture as a prototype of expressionist figural language. The Fallen (1915/16) is considered one of the most impressive anti-war signals of European modernity—a composition that translates the pathos of falling and the dignity of the body into a clear spatial symbol.

Additionally, Standing Youth (1913) and Seated Youth (1917/18) chart the dramatic range of his work: from the aspiring, vertical motif to the introverted, introspective posture. International institutions—including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Leopold Museum in Vienna, the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, and of course, the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg—have displayed key works in their collections or continue to do so today.

Cultural Influence: Modernity, Museum, Memory

Lehmbruck influenced generations of sculptors who understood the human body as a medium of existential experience. His statuary calmness, the soulful penetration of the figures, and the precisely calculated distortion of proportions became signatures of modern sculpture. Curatorial and museum expressions of this influence manifest in retrospectives, collection presentations, and research projects that trace and communicate his artistic development—from early works to late style.

A visible monument to this influence is the Lehmbruck Museum in Duisburg, whose building was conceived by Manfred Lehmbruck in the 1960s. Architecture and collection form an unit that sharpens the perception of body, space, and light—all in line with the sculptural thinking that Wilhelm Lehmbruck shaped.

Oeuvre, Collections, and Critical Reception

Lehmbruck's oeuvre includes sculptures, drawings, etchings, and a few paintings. The discography of his art—his catalog raisonné—centers around the key motifs of humility, introspection, uprightness, and fall. Critics have emphasized since the 1910s the "melancholic dignity" of his figures, their "silence," and "spiritual charge." In the 1970s, major American museums honored his work with overview exhibitions that solidified his position in the transatlantic canon. Later retrospectives deepened the analysis of style, material questions, and the relevance of his anti-war motifs.

Overall, Lehmbruck is regarded as a key innovator of European sculpture—not an eccentric, but a master of reduction. His cultural influence extends from teaching practices in academies to curatorial debates on body politics, empathy, and sensuality in space.

Current Contexts: Exhibitions 2024–2025 and Living Presence

A century after his death, Lehmbruck remains present. In 2024, the Lehmbruck Museum celebrated its 60th anniversary with the exhibition "Courage. Lehmbruck and the Avant-Garde," which shed new light on his role in the network of early modernity. Concurrent presentations at the museum addressed freedom, community, and expressionism, allowing Lehmbruck's figural language to engage in dialogue with the present. Accompanying programs, discussions, and educational formats deepened his significance for today's questions of humanity and form.

In 2025, events in Duisburg will build upon these perspectives—from collection discussions to curated series in the museum context. Internationally, his work remains present in significant institutions, featuring iconic pieces such as Standing Youth at MoMA or Kneeling in American and European collections. Museum archives and research projects provide digitized materials that make provenance, work processes, and exhibition history transparent.

Conclusion: Why Wilhelm Lehmbruck Matters Today

Lehmbruck's sculptures are simultaneously quiet and radical. They reduce the body to lines, volumes, and posture—and open a resonance space for empathy, sorrow, and grace. His artistic development demonstrates how profoundly form can negotiate questions of humanity: dignity, vulnerability, hope. Those who experience his works in space feel the precise composition that flows through the figure like a breath.

Experiencing Lehmbruck live—at the Lehmbruck Museum, in international collections, or in thematic exhibitions—means seeing modern sculpture in its most concentrated form. His art speaks without pathos and touches deeply. A visit is always worthwhile—for art lovers, researchers, and anyone who appreciates the quiet dialogue between body and space.

Official Channels of Wilhelm Lehmbruck:

- Instagram: No official profile found

- Facebook: No official profile found

- YouTube: No official profile found

- Spotify: No official profile found

- TikTok: No official profile found

Sources:

- Lehmbruck Museum – Biography

- Encyclopaedia Britannica – Wilhelm Lehmbruck

- Wikipedia – Wilhelm Lehmbruck

- LeMO (German Historical Museum) – Biography

- Museum of Modern Art – Wilhelm Lehmbruck: Standing Youth (1913)

- Buffalo AKG Art Museum – Die Knieende (1911)

- National Gallery of Art – The Art of Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1972/73)

- Leopold Museum – Wilhelm Lehmbruck: Retrospective (2016)

- Lehmbruck Museum – Exhibition Archive (2024–2025)

- Smithsonian Archives of American Art – Armory Show Photo “Kneeling Woman” (1913)

- Wikipedia: Image and text source